Notes from WATERtalks: Feminist Conversations in Religion Series

“Knowing Christ Crucified: The Witness of African American Religious Experience (Orbis 2018)”

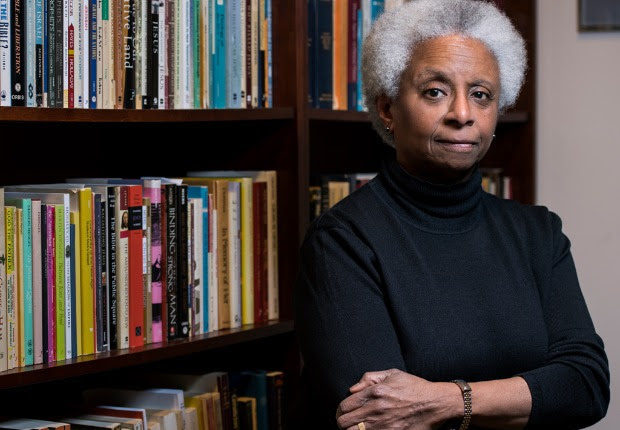

An hour-long teleconference with

M. Shawn Copeland

Wednesday, November 6, 2019

1 to 2 p.m.

Mary E. Hunt: Like all of WATER’s efforts, our purpose is not simply theoretical. Rather, we are focused on changing the cultural and intellectual assumptions that ground discrimination, exclusion, and destruction. This discussion on Knowing Christ Crucified: The Witness of African American Religious Experience is intended to highlight the work of the author, M. Shawn Copeland, as well as to showcase the importance of theological reflection as part of the project of social justice. We chose this volume, this writer, to underscore the signal contribution of African American religious experience as the nexus of “dangerous memory” and contemporary oppression, that out of this might come hope and justice.

Introduction: I am happy to welcome Dr. M. Shawn Copeland to WATER’s table. I wish only that you were here in person, Shawn, so we could celebrate your retirement from Boston College as was done last spring and with such style according to a lengthy article in the National Catholic Reporter. Congratulations on this milestone and every good wish for what is ahead.

I have known Dr. Copeland, whom I will call Shawn, since early in our respective theological careers. I must clarify at the outset that although this book is dedicated to the memory of ‘Mary Hunt,’ it is not dedicated to me. Rather, that Mary Hunt was Shawn’s maternal great grandmother about whom Shawn writes as the person “who first spoke to me of Jesus crucified.” I delight in sharing her name. May her memory be a blessing for me and for all of us.

Shawn retired as a highly respected Professor of Systematic Theology at Boston College, where she earned her Ph.D. in Systematic Theology 1991. She went on to teach at Yale Divinity School and Marquette University before returning to her alma mater. She has honorary degrees from five schools including Fairfield University and the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley in recognition of her outstanding scholarship.

Shawn is the author of three books: Knowing Christ Crucified: The Witness of African American Religious Experience (Orbis, 2018) that we will discuss today; Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being (Fortress, 2010), and The Subversive Power of Love: The Vision of Henriette Delille (Paulist, 2009), as well as coeditor of four theological volumes: Grace and Friendship: Theological Essays in Honor of Fred Lawrence (Marquette, 2016), Uncommon Faithfulness: The Black Catholic Experience (2009), Feminist Theologies in Different Contexts (SCM/Orbis, 1996) and Violence Against Women (SCM/Orbis, 1994).

She has published scores of articles and essays and given more than fifty named lectures. Her own work has recently been featured in a volume edited by Michele Saracino and Robert Rivera: Enfleshing Theology: Embodiment, Discipleship, and Politics in the Work of M. Shawn Copeland (Fortress, 2018).

Dr. Copeland is the past president of the Catholic Theological Society of America (CTSA); past convener of the Black Catholic Theological Symposium (BCTS). She is the recipient of numerous awards, including the CTSA’s John Courtney Murray Award for Distinguished Theological Achievement (2018); the Ann O’Hara Graff Memorial Award from the Women’s Consultation in Constructive Theology at the CTSA (2014); the Marianist Award from the University of Dayton (2017).

Most important, she is a teacher’s teacher, someone who has mentored, advised, and served on countless committees. She has shown the way a scholarly career in theology can be constructed including daily life in a faith community and constant, deepening dialogue with a faith tradition.

We turn to her latest book, Knowing Christ Crucified: The Witness of African American Religious Experience (Orbis, 2018). Some will recall that WATER blurbed it on our website under “What We’re Reading” as follows: “Highly esteemed Catholic theologian M. Shawn Copeland is more than a reliable witness. She is a skilled academic who knows how to weave the threads of oppression into the new fabric of justice, using historical, theological, musical, philosophical, and faith-filled resources. She honors both the legacy of African American slaves and the 21st century #BlackLivesMatter movement. In this clearly written, accessible book, the praxis of solidarity is the meaning of discipleship.”

This is not an easy book. It is one that will bring you to tears given the hard issues at hand—slavery, social injustice, crucifixion in its many forms, the legacy of Jim Crow lived out in our day, and so much more. It is well worth reading.

NOTES on the talk by M. Shawn Copeland

Shawn began with the autobiographical genesis of the book, including reference to her great grandmother Mary Hunt whom she asked about Jesus. “Jesus died for us,” her great-grandmother replied. After a summer school course on world history, the twelve year-old Shawn was deeply appalled by Hitler’s effort to exterminate the Jewish people. The big insight she gleaned from this course was that “people who do not like you, can have power over you and they can kill you.” She realized that theology might have subversive potential for the betterment of all, a commitment that animates this book. African Americans are not only people who suffer. Demeaning treatment of immigrants, those in Myanmar, those who are subjected to police brutality are all among the sufferers. Gradually, she grew to understand the theological vocation as a call to understand suffering.

She turned attention to Chapter 4, “The Dangerous Memory of Chattel Slavery,” in order to find resources to deal with public suffering/social oppression. She cited the influence of scholar Iris Marion Young in considering oppression in liberal/neoliberal societies. Young argues that oppression in such societies takes five forms: economic exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence. Further, in these liberal/neoliberal societies, social oppression too often is invisible for many of us. These oppressions masquerade as ‘the way things are;’ and, these oppressions have deep and lasting consequences not only for the oppressed, but for oppressors as well.

Some theologies can serve as a justification for racism and colonialism. Why do we stand silent at some events? Theology must not remain silent or complicit in the face of suffering. Theology needs to name the damages people endure. The murderous crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth reminds us of the murderous crucifixion of all poor and marginalized people.

Shawn has relied on the work of German theologian Johann Baptist Metz to explore “dangerous memory” as a component of theology. Separating immigrant children from their families, caging children, ignoring children’s health are not new problems. These things were done to indigenous peoples and were done during the time of chattel slavery. Indigenous children were taken from their parents and placed in boarding schools, were abused physically and sexually. African American children were taken from their parents, tortured, and sold. Placing a people’s memory before the Cross of the Jewish Jesus is a theological act. She underscored discipleship as starting point for reflecting upon and dealing with memories.

It must be recognized that slavery was part of early Christian life. Re-membering the Body of Christ is a way to make it whole again. The murder of nine Black people by a white man in a South Carolina Church (2015) raises anew the questions of crucifixion and resurrection.

Johann Baptist Metz, Jürgen Moltmann, and Dorothee Soelle are German theologians who raised theological questions in light of the Holocaust. They proposed various forms of political theology at the same time that liberation theology was emerging in Latin America. Shawn observed that some of our U.S. colleagues who focused on Latin American liberation theology did so at the expense of not looking at structural injustices in our own US society and especially at Black theology.

Discussion

1. One participant spoke of the new movie about Harriet Tubman (“Harriet,” 2019) and the new center, the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center (https://www.nps.gov/hatu/planyourvisit/index.htm) in Maryland.

Shawn suggested other ways to get at social memory, including the film “Twelve Years a Slave” developed from the slave narrative of Solomon Northup (2013).

2. Another person spoke about women’s spirituality programs, many of which are not Christian but focused on social justice. She asked about having ecumenical dialogue among people who want to see justice but do not share the same faith perspective.

Shawn replied that ecumenical conversation is easy since Christians have a great deal in common across denominations. Interfaith discussions are more difficult. However, no matter how the Supreme Being is identified, most religions believe that humans are made in the image/likeness of God. She cited the Golden Rule which is quite common– behaving toward other humans in ways we would like to be treated. Working for justice together does not mean one must become Mormon, Muslim, or Sikh, but for those who are Christian, to work as such with all. After all, Thomas Aquinas was a student of Muslim writers in his time.

3. A caller described her own hope that populations marginalized in the Trump Administration might find ways forward. Black Churches can be a place to find who God is and how God acts to produce a seed of hope for radical action.

Shawn replied to the question of how people get to some sense of God, resurrection, hope by saying that theologians reread history and try to connect the dots. All people have worshipped something greater than themselves. Once people from the continent were herded into slave ships, they were no longer identified as Igbo or Fulani or Ashanti or BaKongo, but as Africans. But before chattel slavery, cultural exchange and cultural mixing was not foreign to these peoples. These peoples had a relationship with God. How that came about we do not know precisely, but we know that they were critical of slaveholding Christianity. We do know that many West African cultures had a notion of a ‘High God,’ who communicated to people through various intermediaries or spirit messengers. This notion of a High God made it possible for them to grasp the Christian notion of One Almighty God. But how did these enslaved peoples come to accept Christianity? Again, we do not know, but I would like to suggest that they ‘converted’ the Christian God to their cause. They grasped that this God was the God of Exodus, the God of Freedom––so why not embrace this God, pray to this God for their own Freedom (The great Spiritual, ‘Go Down Moses,’ sings as much.). Moreover, the enslaved people invested their hopes in the person of Jesus, teaching one another late at night, listening carefully and critically (skeptically), learning and embracing the Bible when they were able to read. For example, in the Book of Amos, we learn of God’s care for other people.

4. The moderator inquired about the Trump years and their overlap with the Roman Catholic Church’s implosion over clerical sexual abuse and its coverup, wondering how Shawn sees parallels or differences in the dynamics of oppression/liberation with which we struggle as Americans, especially African Americans, and as Catholics, especially as African American Catholics. How to make sense of DT’s best poll numbers (46%) and people still giving money to Catholic parishes even as many are closing and all of them are expected to pay the lawyers’ fees for abuse cases of which we have seen but the tip of the iceberg? How does this social injustice persist?

Shawn called it a point of conversation and prayer. It is difficult to square that we are all made in the image and likeness of God with abuse of children, women, immigrants, anti-Black racism. None of this matches up with Christian statements of equality. Fear seems too simplistic an explanation. Backlash to a Black man as President could be a reason for it. Shawn said that she is concerned with the republic, but that sometimes, she says to herself, “I am too old and too black to cry over the United States;” but she does, since the US currently is not (may never have been) what it is supposed to be. She mused over a conversation with a student, as to whether or not it is useful to save something that was rotten from the beginning. She prays each morning for good government, for the healing of the earth––the lakes, oceans, forests, hills, the animals, and so on. We align ourselves with hope by truth telling. Quoting the late womanist theologian Katie Geneva Canon, she affirmed caution: “Even when they lie they lie.”

WATER thanks Dr. Shawn Copeland for a marvelous hour. We look forward to more time together.

Click here for an audio recording of this session.