Catholic women‘s history in Catholic women’s hands

by Mary E. Hunt

Originally published in National Catholic Reporter, September 20, 2017.

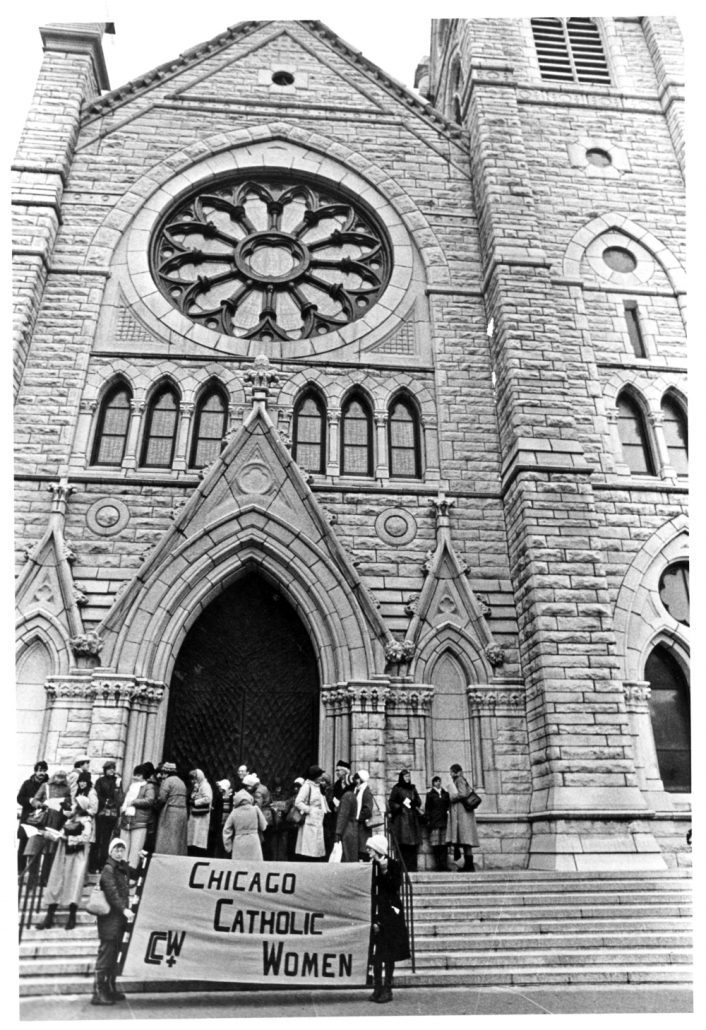

Catholic women’s history fades as fast as we make it because few people write about it. Donna Quinn in Chicago Catholic Women: Its Role in Founding the Catholic Women’s Movement and Marian Ronan and Mary O’Brien in Women of Vision: Sixteen Founders of the International Grail Movement reverse the tide in volumes that provide rich data for future scholars to analyze. They provide details of people, places, events and trends that shape an ever so slightly more inclusive, if still quite exclusive, church.

Chicago Catholic Women spent 25 years, from 1974 to 1999, being a vibrant source of action and inspiration on issues related to women’s equality and anti-racism. The group was source of exasperation and challenge for kyriarchal clerics who cowered in the face of strong women. In the early years, bishops still met and spoke with Catholic feminists, a practice that has long since gone out of vogue as the men became increasingly terrified and embarrassed by the reactions to their outrageous oppression of women.

I had forgotten, until Quinn’s book reminded me, that Pope John Paul II told church housekeepers to give thanks for their vocation to cook and clean for priests so the men could do their important work. I missed the fact that Chicago Cardinal John Cody forbade Maryknoll Sr. Melinda Roper from preaching in her home parish after the murder of her sisters and colleagues in El Salvador in the early 1980s. No wonder Chicago Catholic Women, and many groups like them around the country, including the Women’s Ordination Conference and Catholics for Choice, sprang up in opposition. Thanks to Quinn’s records — culled from her meticulous files at the Women and Leadership Archives at the Gannon Center for Women and Leadership at Loyola University in Chicago — women’s work will not be lost.

Instead, we know who served on every board and committee of Chicago Catholic Women. We know that the women left empty chairs on stages with the names of male, usually clerical, guests who did not show up when invited. We know about the “spiritual hunger strike” proposed by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza to have people receive Communion three times a year max. We recall the Mother’s Day Boycott of Chicago churches in 1988. We have the list of women proposed to replace Cardinal Joseph Bernardin when he died in 1996. The full text of Mercy Sr. Theresa Kane’s famous welcome to the U.S. to Pope John Paul II is here for the reading.

These creative, courageous, always-bold moves were precursors of contemporary strategies for church change. For example, local seminary collections often got “funny money” in the basket, fake bills with pictures of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, who is alleged to have considered ordination for herself. Now, the Lucile Murray Durkin Scholarship for Women Discerning Priestly Ordination is real money given for the first time this year to three women in seminary.

In recent years, Quinn was discouraged (maybe forbidden?) by religious authorities from acting as an abortion clinic escort or a “peacekeeper” as she would have it. Instead, she became the coordinator for the Illinois chapter of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, hardly a concession. Progress is slow for Catholic women, but the real stuff is not just defying the male-only norm. Rather, it comes with a feminist twist — humor, inclusiveness, opening a new way.

I can quibble with Quinn on a few details — Women-Church started off as Woman Church and later changed its name to the plural form to reflect diversity. Activist Sr. Marge Tuite’s funeral was at the Church of St. Vincent Ferrer in New York City, not at St. Dominic’s as Donna reported. But Donna got the big stuff right. Women-Church Convergence remains a force for social and ecclesial change. And yes, the Dominican pastor had the nerve to blather to the ecumenical congregation at Tuite’s funeral that only Catholics “who had prepared themselves” (as I recall vividly) could receive the Eucharist. History should also record that he descended the pulpit without staying for the Mass, and many people who were well beyond his stingy, inhospitable category received the Eucharist “in memory of her.”

Ronan and O’Brien’s profiles of Grail women are equally durable and useful as a trove of information that is the stuff of future doctoral dissertations. They offer a synthetic look at the history and trajectory of the Grail movement. In 1921, a Dutch Jesuit, Jacques van Ginneken, founded the Women of Nazareth, now known as the Grail. It was a group of laywomen dedicated to the conversion of the world with special attention to women and children.

Complicated canonical categories aside, the Grail is not a religious congregation or religious institute. It is a “pious union” which is a lay (not clerical) and secular (not religious) organization that has minimal ties to Rome, explicit women’s leadership, and no clerical chaplain or spiritual director to tell women how to behave. Grail women decide those things for themselves. While Catholic in origin, the International Grail admitted a Swedish Lutheran group. Protestant, Jewish and Buddhist women and women of other faiths are now part of the movement.

Each of the 16 women profiled, from Dutch powerhouse Lydwine van Kersbergen to the Tanzanian leader Honorata Lubero Francis Mvungi who worked with Masai women dealing with female genital mutilation, could be the subject of a complete biography. Readers learn how each one “met” the Grail. For many of the interviewees, the Grail was love at first sight that never abated over decades of commitment to the group.

This book, begun in 2003 by O’Brien and finally finished by Ronan and colleagues in 2017, was initially intended to be a biography of van Kersbergen, a central figure in the expansion of the Grail around the world. But in typical Grail fashion, she insisted that the focus not be on her personally, but on the many women who make a movement of now 850 members in several dozen countries.

Still, van Kersbergen, who met the Grail in the Netherlands and then helped to plant it in Australia and the United States, was a strong force. She traveled extensively all over Africa and to Mexico where she encouraged women to develop local Grail groups and to live out the vision of international community. She was a woman aware of her own power, sometimes overwhelming to others, but always promoting “women for women.”

Rachel Donders, another Dutch woman, was the first international president (1949-61) of the Grail. Her cosmological vision long predated today’s interest in that approach. She started a house of prayer in Israel in 1974 and lived for some time in Portugal. That country’s first woman prime minister, Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo, a chemical engineer by training, became a member of the Grail after her Catholic Action experience as a university student. She brought remarkable political insights and experience to the Grail movement.

Many of these early women were attracted to the Grail’s intellectual life, liturgical innovation, lay apostolate, and social action without the constraints of vowed religious life. In fact, the Grail does have what is called “the Nucleus,” a category of membership that includes vows similar to religious communities. However, especially in the United States, Grail membership has become much more uniform without many people in recent memory joining the Nucleus.

Belgian member Marie Elizabeth (Mimi) Maréchal followed her Grail path to Japan where she studied and embraced Zen Buddhism. Deep respect for Japanese culture led Grail women to realize that they could not grow the Grail in Japan without engaging in cultural imperialism. Unwilling to act in such a way, Mimi went back to the Netherlands where she had trained at the Grail center, the Tiltenberg. With U.S. Grail member Carol White, Mimi led that center for years, adding a Zen dimension to the European Grail. The mix of Catholicism and Buddhism was a rather happy one.

African Grail women, including Ugandan Grail pioneer Elizabeth Estencia Namaganda, form some of the most vibrant local groups today. Tanzanian and South African Grail members are involved in many social and religious projects that foreground women’s leadership and spiritual search in countries where patriarchal Catholicism prevents meaningful religious leadership by women.

These stories form a gestalt of committed, creative, communally connected women that is the contemporary International Grail. Of course I want more — the story of Janet Kalven, a U.S. Grail educator who brought feminist scholars of religion together; the remarkable history of South African Anne Hope and U.S. Grail member Sally Timmel, who wrote the world-famous Training for Transformation series of books used extensively to empower poor people to learn how to act for themselves. But those will perhaps come in a later volume, given this good start.

Both of these books encourage readers, especially women, to write our own histories, to profile our own pioneers lest our history be lost. In fact, since the U.S. Grail and Chicago Catholic Women have been part of the Women-Church Convergence, there is a story to be written about that coalition.

There are built-in problems when we tell our own stories — memories are fallible, biases are obvious, critical distance is missing. But not telling our own stories guarantees they will die with us, which is the bigger danger.

Thanks to these authors, I know what my colleagues and I need to be writing in the next few years. Then, when the later critical analysis is done, at least women will have had a hand in shaping the data, in telling it like it was.

[Mary E. Hunt is a feminist theologian who is co-founder and co-director of the Women’s Alliance for Theology, Ethics and Ritual (WATER) in Silver Spring, Maryland.]