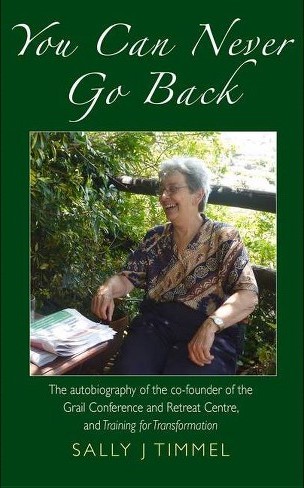

You Can Never Go Back: A Trail of Awakening Consciousness

by Sally Timmel

—

Preface

by Mary E. Hunt

More than a memoir, Sally Timmel brings a dispassionate eye to her life story as a creative, effective activist. She unrolls the blueprint of a mid-twentieth century U.S. woman who grew beyond a parochial midwestern upbringing into a global citizen before most people knew such passports existed.

Her early insight into the different circumstances of those who are rich and poor, privileged and oppressed began a lifelong pursuit of empowerment and justice. Education at a women’s college and work with the YWCA, later with Church Women United, provided Sally with a firm feminist intellectual and activist foundation even if the vocabulary for it came later. A stint in the Peace Corps in Ethiopia and subsequent travel in the Far East made her aware of the toxicity of colonialism and the power of solidarity.

It took falling in love with her longtime partner Anne Hope to nudge Sally in even broader, newer circles. Membership in the Grail, an international women’s organization, provided Sally with additional platforms to actualize her many talents. She and Anne worked for years in Africa, especially South Africa and Kenya, to create Training for Transformation, a movement “working for social justice through grassroots community education. Sally became what she terms a ‘social inventor,’ following her teenage dream of becoming an inventor but of projects, organizations, and social change instead of things.

As an international couple, not to mention as two women, who were in disfavor in several countries because of their commitment to overcome apartheid and bring about free societies, they learned to be creative to thrive. Creative they were time after time, project after project, move after move, living simply but well.

Sally is a doer, someone who has never met a challenge she could not find five ways to meet. This gave her the ability to meld in ideas from her teammates and take in new information even though she did not take “no” for an answer. Yet she is rigorously honest about her own limitations. In midlife, she realized she needed to attend to her own health, and find her own path independent of Anne. So she did, and when they resumed their common life several years later it was healthier and perhaps more productive than ever. Contrast that with so many clueless activists who are married to their work, the cause, at the expense of themselves and their loved ones.

Sally writes as if her biography were just another story of a woman of a certain vintage. But astute readers will realize that hers is a remarkable life, an example of how consciousness keeps expanding and justice keeps gnawing. She is like other wonderful women of my acquaintance, many religiously related whether nuns, Grail members, or Protestant church women, who had similar experiences. They traveled widely, developed deep and long-lasting commitments to countries and people that others still cannot find on a map. Their contributions as workers, role models, and now as sages have shaped those of us who follow.

Thanks to Sally for laying out the contours of an activist vocation. Special thanks for embodying the words of Spanish Jesuit Superior General Pedro Arrupe:

“What you are in love with,

what seizes your imagination,

will affect everything.

It will decide what will get you out of bed in the morning,

what you do with your evenings,

how you spend your weekend,

what you read, who you know,

what breaks your heart,

and what amazes you with joy and gratitude.

Fall in love,

stay in love,

and it will decide everything.”

Sally fell in love with the world. She stayed in love with Anne Hope. And what a difference it all makes.