Learning from “Lady Parts”

by Mary E. Hunt

Originally posted for Feminist Studies in Religion

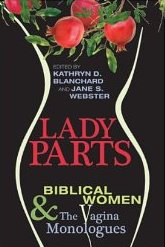

Teachers need vivid imaginations to keep students interested and materials fresh. Kathryn D. Blanchard and Jane S. Webster demonstrate creative pedagogy and innovative scholarship with Lady Parts: Biblical Women and the Vagina Monologues (Eugene, OR: WIPF and STOCK, 2012). This is a unique project both in content and method. It is bound to generate others like it and, with luck, change lives. Various women from Hebrew and Christian scriptures are brought alive by 21st century scholars, students, and others.

The texts of Lady Parts are hard to read. It is not because they are poorly written, nor because they are uninteresting. To the contrary, I found them painful. Stories of ripped, torn, abused, bloodied, mistreated, ignored vaginas are not easy to read. I hope they never become so, because a major goal of the book, according to the authors, is to stop violence against women. One cannot stop something one does not know about.

Most people turn to the sacred scriptures of their faith with the hope of finding insight, enlightenment, even encouragement. Alas, what shines through here is the way in which women, Christian and Jewish among others, have been mistreated for millennia: violated, raped, used, objectified, and thrown away for newer models. Admittedly, the Lady Parts stories, based on scripture, were written by late modern women whose own experiences and awareness lie behind the telling. But I was left to wonder if there is no lovely text in Hebrew and/or Christian scripture where the vagina is enjoying her dear self, safe and snug in her woman’s place, ready for the pleasure for which she was created. Apparently there is not. Gender oppression is ubiquitous and there is no reason to think scriptures would be exempt.

I was heartened to find a few lesbian scenes in the texts. I detect that the roots of Dolly Van Fossan’s piece, “Eve,” in Lady Parts may be in Judith Plaskow’s famous myth about Lilith. Dolly makes the women’s relationship explicit, stretching our imaginations to encompass a new possibility in the text. This is a welcome advance in the 21st century for which Dr. Plaskow’s extraordinary creativity forty years earlier prepared the way.

That Eve and Lilith enjoyed themselves now seems to be an obvious interpretation. I went back to Judith Plaskow’s classic, The Coming of Lilith: Essays on Feminism, Judaism, and Sexual Ethics (Boston: Beacon Press, 2005, especially pages 31-32 where the original myth is reprinted), looking for hints and glimpses that only a lesbian hermeneutic would reveal. There they were, though I had all but missed them in many readings.

Read the text: “before Lilith got away, Eve got a glimpse of her and saw she was a woman like herself…Another woman! The very idea attracted Eve. She had never seen another creature like herself before. And how beautiful and strong Lilith looked!” So Eve noticed the other woman. That was a good sign.

Later in the text: “One day, after many months of strange and disturbing thoughts, Eve wandering around the edges of the garden…swung herself over the wall. She did not wander long on the other side before she met the one she had come to find, for Lilith was waiting.” So, apparently it was a two-way street. Lilith was also interested. Nice.

Their conversation ensued: “They taught each other many things, and told each other stories, and laughed together, and cried, over and over, till the bond of sisterhood grew between them.” What a nice way to describe their pleasurable times together. How had I missed it before?

Toward the end the text reads: “And God and Adam were expectant and afraid the day Eve and Lilith returned to the garden bursting with possibilities, ready to rebuild together.” It sounds like the afterglow of a very special time to me. The males had reason to worry because they were both unnecessary to the women’s pleasure and a source of distraction from the women’s plans.

The reader’s eyes are opened to possibilities that might have been passed over in previous encounters with the texts. Broader and more inclusive understandings of sexual orientation and gender identity inform the task of biblical study. A lesbian/queer women’s hermeneutic is welcome. When will this be taught as a normative part of biblical scholarship in seminaries and graduate programs?

I urge widespread use of the text as a teaching tool, starting with the very extensive Introduction (a useful stand-alone piece for teaching) in which the authors lay out the basic contours of feminist biblical scholarship. They underscore the importance of a feminist methodology, relying on Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza’s four-fold approach to biblical work: suspicion, resistance, remembrance, and reconstruction (Bread Not Stone: The Challenge of Feminist Biblical Interpretation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984). They clarify the importance of using contemporary literary pieces, especially “The Vagina Monologues,” to capture attention and spark creativity among students and colleagues in the field.

Lady Parts reminded me of another creative project of similar proportions, Eve’s Big Fat Family Reunion, a play with music and lyrics by Lois Cecsarini, first performed in 2012, which I reviewed here. Cecsarini’s script is far tamer than Lady Parts, but the message is parallel: women need to live into their power and be strong.

In her piece, Eve and Lilith sing about themselves:

“When it comes to that thing called obedience

My sister’s no fool (oh, no, no fool)

She knows in the end its virtue depends

Entirely on who writes the rules.”

Lady Parts and Eve’s Big Fat Family Reunion, point out the horrible ways women have been treated in texts that are central to major religious traditions. No wonder religion and violence have been such common bedfellows. Creators of these feminist works invite scholars to probe the texts, and to write some new ones, to create alternative images and symbols that exalt women’s bodies, and in so doing to create a safer world. I commend these works to our collective reading and viewing. Enjoy!